Retinal Dystrophy: Genetic Therapy Gives Infants Life-Changing Improvements in Sight

In a UK study, four children (1.0–2.8 yrs) with severe retinal dystrophy from biallelic AIPL1 mutations achieved life‐changing sight improvements. Led by UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and Moorfields Eye Hospital, these early findings support further exploration of gene therapy for inherited retinal diseases.

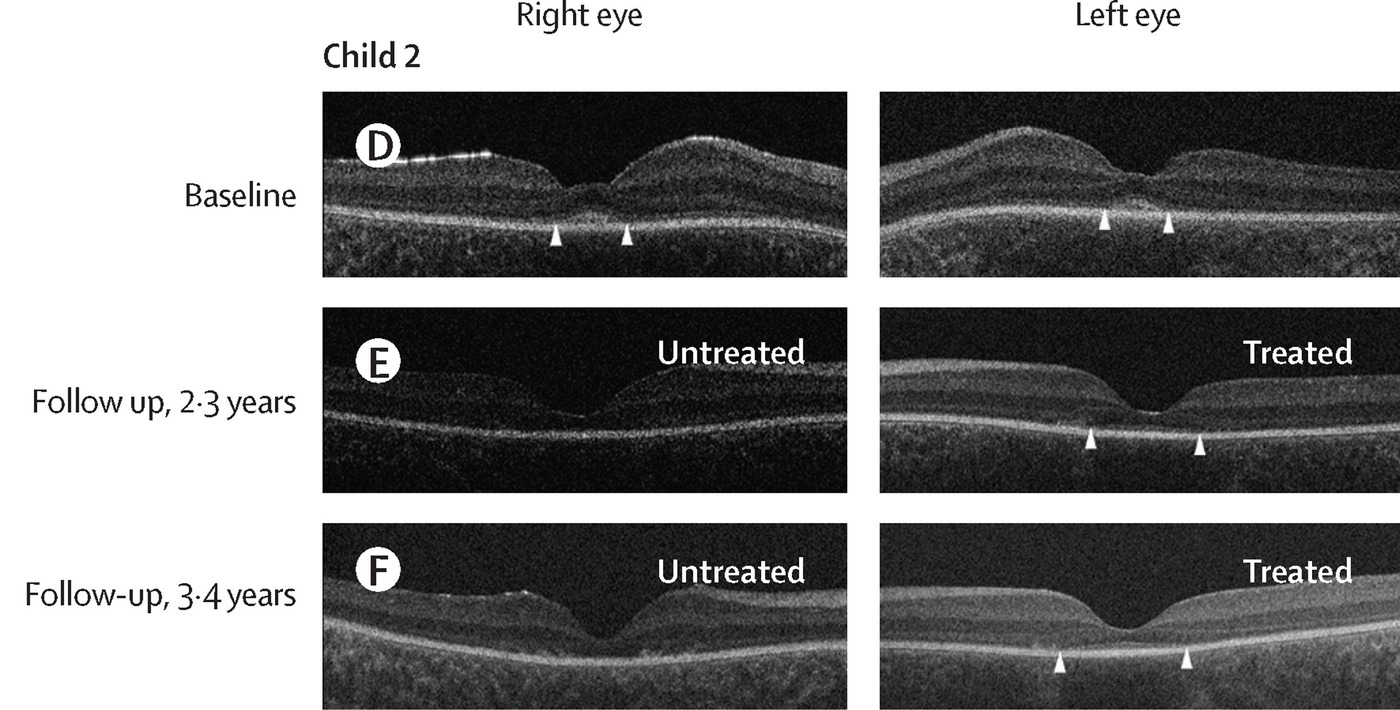

Infants with disease-causing variants in AIPL1 are affected by severe and rapidly progressive impairment of sight from birth. In a cross-sectional survey including 42 individuals aged between 6 months and 43 years with AIPL1-related retinal dystrophy, the sight of the affected individuals was limited to perception of light. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging identified relative preservation of outer retinal structure at the fovea only in children younger than 4 years. This preservation of viable foveal photoreceptor cells in early life indicates a window of opportunity for potential benefit by gene supplementation therapy.

The gene defect causes the retinal cells to malfunction and die, with children affected being legally certified as blind from birth. The new treatment is designed to enable the retinal cells to work better and to survive longer.

The procedure, developed by UCL scientists, consists of injecting healthy copies of the gene into the retina through keyhole surgery. These copies are contained inside a recombinant AAV vector, that can penetrate the retinal cells and replace the defective gene.

The condition is very rare, and the first children identified were from overseas. To mitigate any potential safety issues, the first four children received this novel therapy in one eye only. All four saw remarkable improvements in the treated eye over the following three to four years, but lost sight in their untreated eye.

The outcomes of the new treatment, reported in The Lancet, show that gene therapy at an early age can dramatically improve sight for children with this condition – one that is rare and particularly severe. These new findings offer hope that children affected by both rare and more common forms of genetic blindness may in time also benefit from genetic medicine.

The intervention was generally well tolerated with no serious adverse events. Apart from cystoid macular oedema affecting the treated eye of one child, there were no safety concerns.

The team is now exploring the means to make this new treatment more widely available.

Retinal structure evaluated by OCT: Horizontal OCT scans of the central retina for child 2 (D–F) before intervention and at two timepoints after treatment. The extent of preserved outer retinal structure is labelled with arrowheads. In all children, before intervention, there is evidence of bilateral central preservation of outer retinal layering to some extent (D). In Child 2, preservation of outer retina was evident in their treated left eye at 2·3 years (E) and 3·4 years (F) after intervention but was not apparent in their untreated right eye.

Image: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02812-5

Professor Michel Michaelides, professor of ophthalmology at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and consultant retinal specialist at Moorfields Eye Hospital, commented: "We have, for the first time, an effective treatment for the most severe form of childhood blindness, and a potential paradigm shift to treatment at the earliest stages of the disease. The outcomes for these children are hugely impressive and show the power of gene therapy to change lives.”

The parents of one of the children, Jace, from Connecticut, USA, shared details of their experience with the experimental treatment, which they were accepted for after Jace was diagnosed with an aggressive form of LCA (Leber Congenital Amaurosis).

Jace’s mother DJ said: “After the operation, Jace was immediately spinning, dancing and making the nurses laugh. He started to respond to the TV and phone within a few weeks of surgery and, within six months, could recognise and name his favourite cars from several metres away; it took his brain time, though, to process what he could now see. Sleep can be difficult for children with sight loss, but he falls asleep much more easily now, making bedtimes an enjoyable experience.”

The treatment was developed and manufactured at UCL under a Manufacturer’s ‘Specials’ Licence (MSL) held by UCL. MeiraGTx, a UCL spinout supported by UCL Business (UCLB), the commercialisation company for UCL, supported production, storage, quality assurance and released and supplied it for treatment under the genetic medicine company’s MSL.

The procedure to administer the treatment to the affected children took place at Great Ormond Street Hospital. The children were assessed in the NIHR Moorfields Clinical Research Facility, and the NIHR Moorfields Biomedical Research Centre provided infrastructure for the research.

Source: UCL / The Lancet

Michel Michaelides, Yannik Laich, Sui Chien Wong, Ngozi Oluonye, Serena Zaman, Neruban Kumaran, Angelos Kalitzeos, Harry Petrushkin, Michalis Georgiou, Vijay Tailor, Marc Pabst, Kim Staeubli, Roni O Maimon-Mor, Peter R Jones, Steven H Scholte, Anastasios Georgiadis, Jacqueline van der Spuy, Stuart Naylor, Alexandria Forbes, Tessa M Dekker, Eugene R Arulmuthu, Alexander J Smith, Robin R Ali, James W B Bainbridge, Gene therapy in children with AIPL1-associated severe retinal dystrophy: an open-label, first-in-human interventional study, The Lancet, Volume 405, Issue 10479, 2025

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02812-5.